by Henry Fleming

‘Classical’ & Sporting Equitation Diverge

“When I was staying in Berlin, I saw German horsemanship practised in all its entirety and as I have no wish to pose as a critic, I will merely say that the principles practised in Prussia are diametrically opposed to mine; for instance several officers who were noted as horsemen said to me “We like our horses to be in front of the hand, and my reply to them was that I like to be behind the hand and in front of the legs, so that the centre of gravity is placed between these two aids, as it is only on this condition that the horse is absolutely under the control of the rider, that his movements will be graceful and regular and that he will change easily from a fast pace to a slow one whilst preserving his balance; because, as I told them, every horse who is in front of the hand is behind the legs and consequently escapes control at both ends, so his movements cannot be either graceful or regular; furthermore, if he has a vicious conformation, how will you put it right?”

– Baucher

So began an unresolved controversy between adherents of the two major schools of thought pertaining to the finishing of high school dressage horses.

Today, we perceive a superficial conflict between “classical” and “competitive” dressage, but these are very modern categories which did not exist for Baucher. Since Newcastle’s time, high school dressage had been esteemed as both a fine art and a martial art. Indeed, there was what was called “outdoor horsemanship”, which referred to the more pragmatic and less refined notions of racing, hunting, and campaign (mounted cavalry) equitation, but the notion of a high school dressage “competition” would have seemed as strange to Baucher as it would have to La Guerenier and Newcastle before him.

The competing styles of high school-level horsemanship were represented by Francois Baucher, and the Comte Antoine D’Aure, his aristocratic adversary.

We’ll revisit some of the details of this archetypal struggle later. For now, understand there were only two ways to see high school airs demonstrated in the 1800’s: exhibitions of riding schools sponsored by the nobility (a la the Spanish Riding School of today, as well as the other three remaining national schools of equestrian art), and exhibitions presented by the “circuses” (high brow affairs at the time, routinely attended by nobility, aristocrats, and intellectuals). These “circuses” were unlike the circuses we may remember from childhood. These were grand affairs comprised of the “who’s who” of the day with popular artists as entertainment; the scent of perfumes in the air, all dreamily lit by grand chandeliers, and the sounds of the best musicians. Not so much clowns, screaming babies, and gas-powered generators.

Unsung Hero of High Equitation

Given the thousands of years of horsemanship preceding every master whose opinions and methods have made it into print, we put ourselves at risk the very moment we assert this or that person “invented” anything – whether equipment, a particular technique, or a general method of progression.

The very best our earliest “classical masters” could do – and the very best anyone now living can do – is realize, synthesize, and communicate truths they understand. And this seemingly simple thing – communicating the truth – is actually quite a difficult thing. As C.G. Jung and, before him, Ralph Waldo Emerson, observed: as soon as we come to the very center of a thing – any thing – another center emerges. This is to say, stumbling across singular truths is difficult enough to do for ourselves – and even more difficult to convey to others.

This is true of physics, where every time we think we’ve discovered the fundamental building block of Nature, we find something yet more basic as soon as we try to lock the truth in an objective picture for others to understand. And thus, over the course of science’s wobbly advance, we have leap-frogged from ether, to elements, to atoms; followed by protons, electrons, and neutrons; and, later, quarks, flavors, colors, and so on.

So it is with biology, psychology, history, and any other domain of knowledge we put our shoulder against in an attempt to have to the very last word; the main, indivisible thing. Or the very first one, as it were.

On approach to the bright light, vocabulary constrainsus. Apt words for what we intend to mean do not really exist, leaving us with metaphors and analogies, whichcan only ever berough approximations. In the universe of the voice-boxed biped, we are lucky when our listeners discern a shadow of our real meaning. Know what I mean?

By many accounts – including his – Baucher could do in months what had previously taken others (and still takes others) years to achieve. He significantly raised the bar for a finished high school training standard in terms of time. He introduced new high school movements (airs) such as lead changes every stride (a tempi) – unknown as a standard prior to his exhibitions, which continue to be regarded as among the most difficult feats of haute ecole.

The fact that his methods contradicted many subsequent masters – since the Renaissance (at least as interpreted by ‘the establishment’ during his day) made Baucher a polarizing figure in his time – and he has remained so since among competitors, professionals, and connoisseurs of high school equitation.

Baucher’s Affect

Though I had ridden extensively from my youth – beginning literally before I could walk – it was not until Baucher that I understood what it was to truly wield a horse. Not just start a horse and ride well at the three natural gaits. But wield … as a bionic auxiliary.

Had his concepts been less intuitive or less repeatable; the results less observable, or the effects less durably exponential, I might have dismissed Baucherism as just “another method” – with new terms for the familiar concepts vaguely grasped by any reasonably experienced horseman.

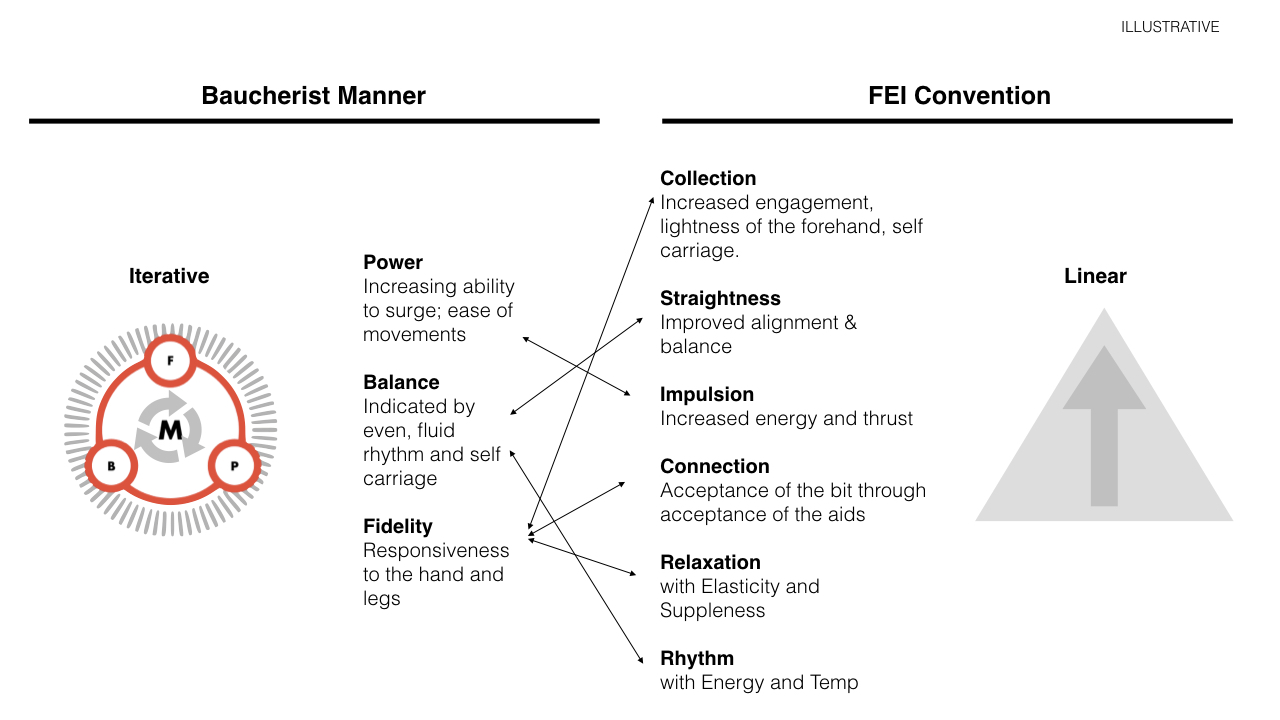

But Baucherism is beyond mere methodology. To borrow Kuhn’s socio-scientific term back from management consultants, Baucher’s system represented a different paradigm – in addition to inverting what had become the traditional order of operations.

His greater contribution – much more important than any particular sequence of lessons – was the observation and explanation of key “truths” with immediate utility for every serious student of equitation. Somewhere between Newton’s gravity, and Emerson’s compensation, Baucher observed the natural fact of an innate equine equilibrium which he repeatedly demonstrated could be made manifest under saddle with a range of horse types (not just Spanish horses which had long been optimized for collection), and which he insisted should be quickly accessible to all equestrians willing to understand and pursue tactfully.

When I finally experienced Baucher’s notion of equilibrium from the saddle, it was as if – after well over 30 years as an avid and skilled equestrian – I had rediscovered the animal we call “horse” entirely. And that was just the teaser.