by Henry Fleming

The bitting progression describes the order in which we introduce?bits to?the horse in training. ?Though the bosal and/or training cavesson (of Californio origins, and of Newcastle’s method, respectively) are not bits per se, they can also have a?place in the course of training.

My personal “bitting progression” starts with the hackamore, then introduces the snaffle. Once the right criteria have been met in the snaffle, I add?the curb quite quickly, dropping the snaffle (bridoon)?altogether within a few weeks. ?Once the horse is confirmed in the curb, we can either remain ‘in the bridle’ (the curb only), or return to the snaffle, depending upon preference. ?Contrary to to popular paranoia, the progression to the curb has nothing to do with increasing control through ‘leverage’. If ‘control’ is an issue in the snaffle, we have no business progressing to the curb. ?Nor will curb bit (used properly) harm the horse’s future manageability in the snaffle – in fact, we will find the opposite is true. ?The different bits introduce different sensations, and expand the horse’s essential working vocabulary. ?Correctly applied, the curb study will only confirm and refine the horse’s responsiveness to the snaffle.

Though we see Francois Baucher often accused of “using harsh bits” by people who?have never actually?read?Baucher, this is untrue. ?In fact, though he moved to the curb quickly during training, he preferred to?’round-trip’ the progression, moving back to the snaffle once the curb was confirmed.

Artificial Aids: ?Avoid Them

I avoid using any other bridling devices to augment the?progression. ?No draw reins*, martingales or tie-downs. ?In my opinion, most often, use of these devices indicates a lack of understanding, knowledge, and/or patience on the part of the rider/trainer. ?All of the auxiliary?training aids I listed are designed to mechanically force or prevent certain behaviors or postures, and though they may mask training failures temporarily, they correct nothing and create new problems?- especially in amateur hands. ?Such artificial aids tend produce artificial results.

The results are “artificial” because they will not stick. ?Remove the low drawn Western-type draw reins for very long?on a horse trained with them, and his head will resume its prior position. ?Remove the martingale (another misapplication of the draw rein) or tie down, and the horse will quickly regress to nosing out and or head tossing. ?The head and neck positions will return to where they actually should be given the horse’s?actual?degree of competence and fitness.

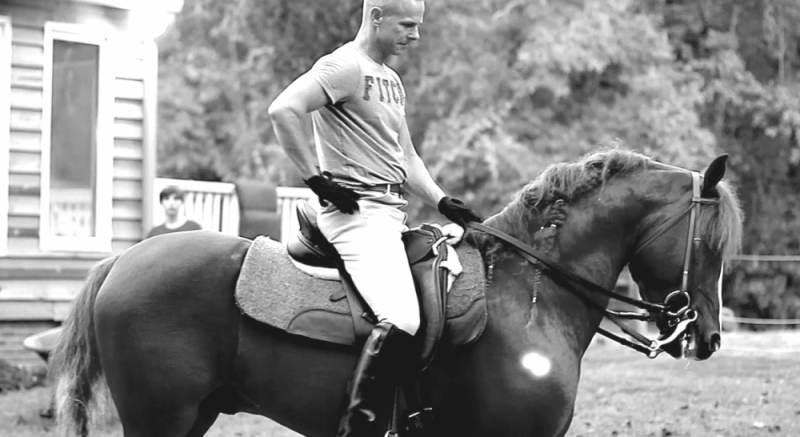

My objective with every horse is to create a willing, predictable mount who carries himself with a?balance that would make Nuno Oliveira smile, is fully responsive to high school equitation, and exhibits no fundamental resistance.

When working with a junior horse, it is impossible to separate his educational development from his physical development. ?That is to say, he must hit certain gymnastic milestones?before he is physically capable of proceeding with higher academic lessons requiring increased strength for sustained collection.

Withers First

Simply put, before we can obtain collection easily, and before the horse can offer it comfortably, we are not working at a high school level. ?Collection?(and not extension) is really the point of departure for high school proper, where high school training (unlike the < Intermediate levels of competitive dressage, comprising some 90% of ‘dressage’ competitors) is the active pursuit of high school competence, evidenced by and enabled?by the collected exercises, or ‘artificial airs’, such as the piaffe.

The most important physical constraint to advanced training is initially the area of the withers – the muscle group the horse uses to lift and hold his neck vertically or “up”. ?Lay equestrians (and most professional trainers across disciplines) are often oblivious to the central importance of the position of the neck (which has nothing to do with the verticality?of the face), and its impact upon the horse’s ability to collect, and ultimately obtain his?equilibrium.

Until I can develop the muscles comprising the area of the withers,?such that it is comfortable for him to work with his neck up instead of out, he will continue to move on his forehand and cannot physically achieve?what Baucher called “equilibrium”. ?We can quickly develop the withers by encourage the horse to work with his head (and thus his neck) raised as high as possible (without becoming “pigeon throated”) at the school walk and school trot during brief, concentrated schooling sessions.

The very last thing I want to do is encourage him to do is? lower his neck. ?As the neck comes?vertical, weight is displaced from the forehand to the hindquarters – which is increasingly where we want it. ?Working with his neck up will quickly strengthen his withers, and, in a complementary fashion, also strengthen his hindquarters. ?In fact – almost by definition – the stronger I can make his withers, the stronger I will have made his hind end. ?The relationship is thus: ?an upright neck position encourages the rear legs travel more under his body, and less behind his body. ?Instead of simply?pushing his mass forward in a straight line, he must do more lifting. ?It is the closest we can come to getting our horse to do squats. ?So, quite?aside from teaching him the notion of collection (which it does), teaching him to work with his neck up will also physically develop him correctly and rapidly.

I begin with a hackamore for a couple of reasons, and none of them have anything to do with the notion of “protecting the horse’s mouth.” ?Instead, I use it because it’s a simple and?intuitive instrument – both for people and horses. ?The signal it transmits is very clear, and the feel of it will be familiar to the young horse who is already comfortable following his nose in a halter. ?Moreover, as my new student begins to develop physically, I find the right muscles tend to develop more quickly in the hackamore, because – used the right way – ?it tends to promote “stage-correct” neck carriage. ?As an added benefit, my horse will automatically be trained to ride with a simple halter from the time he’s a greenling.

I move from the hackamore to the snaffle exclusively for a short period to familiarize the horse with the feel of having a bit in his mouth, and to refine his familiarity with the basic flexions I use to manipulate his posture. ?If necessary, and used properly, the snaffle may also be used to raise the neck carriage further, particularly for horses with a tendency to over-bend their necks prematurely in response to the hackamore. ?At this stage, I remain much more concerned with the position of the neck than the verticality of the face.

The “exit” criteria for the snaffle bit will be:

- Lightness in the snaffle

- An easy responsiveness to both direct and indirect rein aids

- The sense that he “listening with his tongue” and the corners of lips, not?pressure on the bars of his jaw. ?In the latter case, he is necessarily setting his jaw?against me to some extent (however slight) – and therefore, his jaw can neither be mobile nor relaxed … and therefore, he is unprepared to flex correctly at the poll.

As soon as he’s comfortable, I introduce the curb (in addition to the snaffle). ?For all intents and purposes, we’re now in the vaquero’s “two-rein” stage – a technique more or less identical to Newcastle’s curb/cavesson stage in effect.

This could be another article, but, in simplest terms: ?both the snaffle and the bosal (the nosepiece of the hackamore)?tend to serve as a kind of “safety” coupled with a bit which is less forgiving should the horse compromise the hand. ?However, for the purposes of academic dressage, the snaffle (or training cavesson) can offer a more concise means of asking the horse to keep his neck lifted as we introduce a bit with a vertical bias. ?This to say, horses will initially have a tendency to over-bend with the curb – tucking their face too far in, often forcing?their neck carriage too low, preventing their poll from being the highest point of their silhouette.

Such?an?”over-bent” position may win blue ribbons in various classes every day (including dressage shows), but it is, as I have mentioned elsewhere, functionally moronic, and destructive to the self carriage and balance we are working so hard to obtain. ?The snaffle helps us avoid it (by acting on the corners of the lips), until the horse has learned to reliably lift – not just tuck – with the curb as well.

Ultimately, as he develops the correct habitual self carriage, and clearly understands direct and indirect neck rein signaling, I drop the snaffle altogether and ride exclusively with the curb. ?I am in no way “escalating” to the curb. ?That is to say, I am not moving to a curb because the snaffle (or the hackamore for that matter) isn’t “strong” enough. ?The horse and I will have long ago advanced beyond wrestling matches – to the extent we ever had any – by the time I introduce the curb.

The reason for the curb, then, is because it enables a much higher degree of fidelity in my communications with the horse. ?It’s action has a vertical bias, encouraging a correct?ramener, in time. ?The solid mouth piece fosters?”straightness”, and also makes?indirect and neck reining more intuitive.

TBA