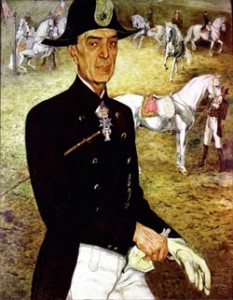

A Teacher’s Teacher

Alois Podhajsky was head of the Spanish Riding school during the malaise of World War II. ?A veteran of World War I, Podhajsky was more hardscrabble than one might glean from the affable tone of his letters today.

He witnessed the decline of mounted cavalry across Europe firsthand, subsequent to mechanization and advanced munitions. ?Nevertheless, Podhajsky succeeded in making a career involving his lifelong love of horses between the wars.

Thanks to his efforts near the end of WWII – which prioritized the legacy and welfare of the animals in his charge ahead of the politics of his time – General George Patton (himself an avid horseman) would go out of his way to ensure the safety of the school’s prized Lipizzaner bloodstock.

I’ll avoid rewriting much of this interesting piece of equestrian and world history here, and encourage you to read his personal accounts. ?Instead, l’ll describe why he matters to me, which, unlike most of the historical figures I highlight, has less somewhat less to do with training horses and more to do with training people.

Podhajsky was a gentleman, and fascinated with horses since childhood. ?He was an expert and capable trainer. ?In practice, his methods and mine would differ, given the obvious implications of the Riding School’s Prussian heritage. ?(That said, no one would have mistaken him as a disciple of the Seeger school. ?He was ever-patient in his methods; treated each horse as a treasure; and went to great lengths to avoid injury in the course of education).

He was incredibly insightful when it came to educating new riders. ?One would expect a German cavalry officer with an equitational education of essentially Prussian origin to consider the rather martial manner many of us know well to be the norm. ?During his time, and still in ours, the process goes too often thusly:

- We put an enthusiastic, smiling new student on a trotting horse (usually a fairly green one – or at least a very dull one – because, of course, we don’t want to risk damaging the training of a more advanced horse)

- They trot uncomfortably around on a longe line, circling an instructor who shouts aloud all their faults.

- Eventually the lesson horse takes a mis-step, or the student inadvertently surprises him, making the first of an eventual few “unintended dismounts.”

- Somewhere between lesson 1 and 4, they are no longer smiling, and no longer enthusiastic.

Podhajsky, instead, covets and shapes the experience of the new rider as carefully as he would the new horse. ?There is no value in scaring new pupils into understanding the value of staying on – unless our intent is to even more rapidly reduce the world’s small population equestrians.

There is much value, however, in nurturing a student’s enthusiasm, and, as a teacher, expanding their enjoyment of equitation, while avoiding letting fear ever overtake the slow advance of skill and experience, and the enduring confidence they will bring.

(It is of course also important to avoid boring students into disinterest. ?And to this end, inevitably, we must acknowledge green riders and green horses are a bad combination. ?But this topic must wait for a separate article!).

Had more new equestrians been started with these principles in mind over the last 50 years, we would have many more old equestrians. ?Thanks to Podhajsky, I constantly remind myself when working with others that it is as important to apply the old horse training adage “I have time” to people as it is with horses.