William Cavendish, First Duke of Newcastle Upon Tyne, is the common denominator among modern schools of dressage. All masters since Cavendish appeal to him, including la Gueriniere.

Gueriniere is widely credited for ‘inventing’ the shoulder-in exercise. He refers to Newcastle’s work frequently, and, factually, Newcastle must really be credited with the ‘shoulder-in’, in effect – the shoulder-in being an adaptation of the Duke’s oblique work on the circle applied to the parade field/rectangle.

Mining the Duke of Newcastle’s insights will be more work than watching ‘clinician’ videos on RFDTV. Absent down-your-throat marketing montages and monster truck music, Newcastle’s manuals will feel challenging for modern readers. To access his intelligence, we have to adjust for the language of the era, the context of his exclusive audience, and the speciality of his intended topic. More generally, we must adjust to the way educated people actually communicated with one another, before the “8th grade reading level” became our litmus test for “understandable writing” – a good rule of thumb for marketeers marketing to the masses, perhaps, but an inefficient means of conveying the complex and sublime (neither being within the purview of 8th graders).

Language

Since the Duke addresses us from 17th century England, you’ll have to acclimate yourself to the nuances of 17th century English language, in addition to the printing peculiarities of the time – particularly the usage of “f” where the lower case “f” may “reprefent” either the letter “s” or the letter “f”, depending upon the context of the word.

Given the challenge and necessity of using complex equivalents to describe the nuanced sensations of high equitation in any era, Newcastle’s works can be difficult to discern for modern readers and riders, now used to a different syntax – now further obfuscated by not only Italian, but more French, and the relatively recent introduction of a lot more German. This is especially so for new students of equitation who will lack the context and experience to understand advanced concepts written in their native language – let alone a hodgepodge comprised of multiple others.

Audience

In addition to his relationship to Charles I (to whom he was a trusted advisor and creditor) and Charles II (whom he taught to ride), understand William Cavendish kept company with and sponsored the products of some of his century’s most notable thinkers.

The small but weighty constellation of philosophers surrounding Newcastle in the context of intellectual friendship and patronage was regarded as the “Newcastle Circle”. It included names at least vaguely familiar to virtually every modern teenager, such as Thomas Hobbes (best known for Leviathon, and, arguably, modern Western political science/philosophy itself), as well as Rene Descarte – well known for his often mis-abbreviated quote I think, therefore I am (which is properly: I doubt, therefore I think … therefore I am), and also responsible for the notion of algebraic geometry and calculus.

A High School Treatise for Experts vs. “Dressage for Dummies”

From the Duke’s standpoint, most modern equestrians would be considered ‘novice’ riders – even most very experienced riders. At the outset, Newcastle announces his work is not for the inexperienced, but seasoned horsemen far enough advanced for his advice to be relevant. Two hundred years later – give or take – Francois Baucher is similarly specific and exclusive in his later New Method, opening his third chapter with:

” … It is understood that I only address men already conversant with the art, and who join to an assured seat a sufficiently great familiarity with the horse, to understand all that concerns his mechanism.”

Francois Baucher

Consider,

Popular ‘Natural Horsemanship’-type clinics tend to focus on the most rudimentary horse-handling and training concepts, producing, on their best days, capable trail riders, but not ecuyers.• Breed shows long ago subordinated meaningful equestrian theory, precepts, and purpose to du jour pageantry.

As for the competitive dressage world, I estimate less than 2% or so of “Dressage” riders compete at levels requiring movements and figures actually associated with high school proper (versus performing routines indicative of a particular kind of preparation for high school) – and even the top 2% compete two-handed in a double bridle, which would have been yet ‘unfinished’ by the 17th century standards.

Newcastle and Baucher both convey a theoretical calculus, as it were – not basic multiplication. Both appeal to equestrian connoisseurs faced with resolving challenges unique finished manege horse-making.

So, even if Newcastle’s text (articulated as it is at a level of sophistication befitting the most educated and elite readership of Western civilization) were presented at the 8th-grade reading level with which today’s more generally literate (and yet less educated) readership has become familiar, most would yet struggle to reconcile the gist of his thinking in the absence of already being solid horsemen, familiar with the challenges unique to high school training.

This is not at all to dissuade you from pursuing Newcastle (and Baucher). On the contrary, it is to encourage you to revisit both should they initially seem inaccessible. As your experience and understanding grows, their advice will begin to resolve.

In Context

Unlike most other historical or modern horsemanship philosophers (excepting perhaps Xenophon and King Eduardo of Portugal), William Cavendish was a prominent and influential military, political, and cultural figure in his day, quite aside from his equestrian passion.

Despite being a very wealthy noble (a creditor to his liege, Charles I ), and an ‘inside’ level courtier, Cavendish was eventually beset with personal, financial, and political misfortunes resulting from the fall of Charles I.

A rising star up until the English revolution, the Duke of Newcastle found himself effectively bankrupt, indebted, and exiled to the European continent, uncertain what would ultimately become of his estates and other holdings in England. Underscoring his love of the horse and the manege, he points out that he took great pains to afford nice horses when affording them was indeed painful.

Resounding throughout his work is an abiding commitment to equestrian truth, a sincere love of the horse – and, endearingly – with the sarcasm and wit of an opinionated friend.

Modern Relevance

Many equestrians casually dismiss Newcastle as a ‘historical figure’, whose methods must somehow be outdated and irrelevant today – after all, look at what a machine gun the musket has become!

Except? Newsflash: Horses are not a new technology.

While muskets have become machine guns since the 17th century, approximately 0 ‘advances’ or discoveries are likely to have been made with respect to horse training. So on what basis should we presume his methods are any less applicable today? There is none – there is the opposite of one.

In effect, Newcastle was a “Baucherist” long before Baucher.

Were we to witness Newcastle’s dressage today, students of ‘classical’ and Baucherist methods would recognize his progression and the finished work as the academic/artistic/romanic type of dressage innovated (or at least assimilated and popularized) by Baucher – in contrast to the Prussian-cavalry derived progression of Seeger, Steinbrecht, et al, which survived to the German cavalry manual of 1912 (the basis of modern FEI-sanctioned contests – and thus the Olympics … and thus all competitive dressage in general).

Academic vs. Competitive Dressage

An academic high school progression (as pursued by Newcastle, and Baucher) begins with lightness, pursues collection immediately, moves through the double bridle and on to the curb alone quickly; promoting a particular notion of the hand and heels, and how the horse should respond to them.

In contrast, modern Olympic dressage inverts various of these classical principals, handicapping the development of self-carriage by teaching the horse to push through the hand (in practice, destroying lightness and self carriage in the interests an artificially fixed poll and – for whatever reason – and obsession with thrust and extension at the working trot). The “end” or object itself has obviously been lost, as the horse never actually graduates from the double bridle! (Why not? Because, while the horse can be conditioned to accept extremely heavy contact with the snaffle bit, he will not accept such contact on the curb, and few modern riders understand how to ride with a curb!).

By historical standards, therefore, the bridle horse – and certainly the bullfighting platform – adhere more closely to the classical manege standard than most modern ‘Dressage’ horses.

Softness, The ‘Fixed Hand’, and Collection

So then here is Newcastle describing the state of the Noble Art during its apex as a fine art, and as one of its most sophisticated practitioners and connoisseurs (pages 180-181 of his second manual):

“The Hand should … [be] … Easy, but Firm; for there is nothing makes a Horse go more of the Haunches, than a Light Hand, and Firm; for when he hath nothing to Rest on Before, he will Rest Behind; for, he will Rest on something; and when he Rests Behind, that’s upon the Haunches: A light Hand is the greatest Secret we Have; but there is no Horse can be Firm of Hand, except he Suffers the Curb, and Obey it.”

– Newcastle

Here, in a single paragraph, we can see Newcastle advocating three core principles of a future Baucherist school:

1. The Priority of Softness (a.k.a. Lightness)

2. The Fixed Hand

3. Equilibrium/Pervasive Collection/Balanced Movement

Baucher’s “Fixed Hand” remains virtually weightless and malleable, as long as the horse willingly gives to it, yet instantly becomes strictly “fixed and immoveable” should the horse resist its action. Only thus can the hand be simultaneously “Light” and also “Firm” as described by newcastle.

To be clear: “Firm” here necessarily refers to the fixity of the hand – not a continuous traction (which so many misunderstand as the “contact” associated with “English” style riding).

This may seem a subtle distinction, but it’s not really. Imagine a dog tied to a pole. He’s a big black Mastiff. He’s sitting there peacefully watching the day. Can you see him?

Suddenly, a white cat scampers by. The dog reflexively bounds to pursue him. Just as he gains momentum, the inevitable: he hits an invisible wall when the length of rope is spent. This is fixity.

The pole never moved. It was not “pulling” when there was slack in the rope; it was not pulling when the slack ran out – it simply stayed where it was.

Now, rewind the scenario. Keep everything the same – except instead of being at the end of the rope tied to pole, he’s at the end of a leash held by a handler. The cat walks by. The dog pursues him. He quickly removes the slack that previously existed in the rope as he charges ahead, dragging his reluctant handler behind him. The handler doesn’t weigh enough to stop the dog, so he leans against the force of the dog, slowing the dogs pursuit, but not stopping him. The handler is now “pulling”. Clear enough?

The Duke is specifically denouncing any tendency of the horse to lean on the bit. This implies the horse must be responsive to it, and never resist or push against it. This, in turn, necessarily implies a relaxed jaw managed by a light, unimposing hand, and the absence of pervasive traction.

Thus, Newcastle distinguishes his actual (high school) dressage from future devolutions, including those committed by future European cavalries – even Prussia’s, which, for reasons having nothing to do with high horsemanship, has become an international and Olympic norm.

His program focuses on lightness, balance, and conditioning as a means of moving weight to the rear (which is to say, moving the hind legs underneath, or “resting on the haunches”) to achieve the essential grail of high equitation: collection. Now, if you have ever taken “dressage lessons”, you will realize this object of “collection” is directly opposed to the du jour fetish of competition dressage: extension and thrust at the trot.

Technical Innovations

Newcastle is perhaps most famous for his innovation of “draw reins” and the “cavesson”, though it would be a grave misinterpretation to think of these items as the devices surviving under the same names today, and in the context which they are most often used today.

The Draw Rein

Let’s address the draw rein first. Experienced horse people are quite familiar with the notion of “draw reins”, and are most likely to associate them with the means some trainers use to achieve artificial head sets – that is, to force their horses to carry their heads in a position that only has cosmetic value in terms of winning basic walk/trot/canter beauty pageants and mounted costume parties, but no (or a destructive) gymnastic benefit.

The position of the head and neck, in such cases, have no actual practical value, have not been achieved through gymnastic progressions which would make that or this position most logical and comfortable for the horse, and will not ultimately contribute to the balance required for high mobility and future high school airs and figures (an infinitesimally small percentage of them will ever experience such equestrian delicacies).

Since the trainer’s objective is to win, say, a Western Pleasure class (where the current fashion implies the horse’s nose all but touch the ground in every gait) running “draw reins” from the the bit through a very low loop or ring near the girth seems to make sense: the rider has so much leverage against the horse’s head, even an adolescent girl in pink chaps can easily and continuously keep even a relatively green horse’s nose forced to the ground.

The Duke’s innovation (and intent) was not this. At all. In addition to the reins going to either the snaffle or the curb, he added a single auxiliary rein attached to a training cavesson. The auxiliary rein was run through a ring at the top of the cantle, typically as a supplement to his inside rein only. The draw rein was used in advance – or instead – of the inside rein to promote softness via signal (not force). The leverage gained via the ring on the cantle was used to support the notion of the Fixed Hand principle (described above), in the event of resistance, and avoided hardening the mouths of young horses just becoming familiar with the bit (and prone to over-reaction and resistance).

Moreover, we can be certain Newcastle’s draw rein was never intended to forcibly lower the head. The illustrations included in his works present horses in training and finished horses. In all cases, one can plainly see the horse’s neck is being/has been lifted (a la Baucher’s “second manner”), and therefore ipso facto draw reins have been used only to better enable the fixity of the hand (vis- -vis the above). Specifically, the draw rein is not used to force the horse’s head into an artificial position (a la virtually every headset seen in every show ring in the US, where the object is a particular silhouette of the head and neck, versus primarily a particular balance and distribution of weight – or, in a word, mobility). To put a finer point on it: Newcastle’s draw reins were not at all intended to enable any moron with a horse and a hat to win future Western Pleasure classes.

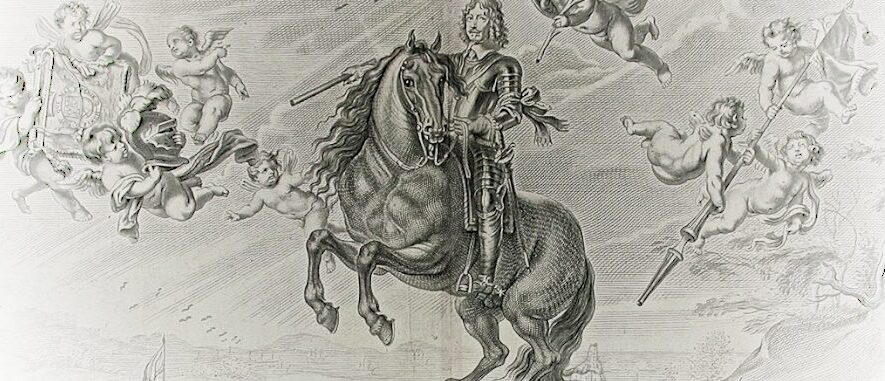

For further evidence, we may simply refer to the numerous plates accompanying Newcastle’s manuals, which show him both training and presenting horses – and observe the tackle in context. That the characteristics visible in his plates represent his ideal (which I think it is safe to presume they do) is, in my view, evidence enough of certain techniques he applied, and by the same token, evidence of techniques he must have avoided. What headgear have the finished horses With elevated necks, moving rassemble, they wear only the curb, are ridden with one hand, and with light, weight-of-the-rein contact evidenced by the visibly loose tension on the reins.

Further, there is no “cavesson” on finished horses – neither the Duke’s training iteration of this tackle, nor the modern muzzle variety … nor even the residual training bridoon (the snaffle component of the double bridle).

There can be little question the Duke’s horses were dressed using a characteristically romanic progression to achieve such ends – and not the more modern campaign-style progression we associate with Prussian horsemanship.

The ‘Cavesson’

Lastly, let’s consider Newcastle’s cavesson. Today, we associate “cavesson” with the noseband of the “English” bridle which, confoundingly, often goes by the same name. This “cavesson” has less than nothing to do with Newcastle’s innovation of the same name – being neither his innovation, nor an evolution of it. The “cavesson” roughly associated with modern “English” riding (as used in the hunter/jumper and competitive dressage domains) is for all intents a muzzle which, instead of being used as interim training device, is a standard piece of tackle from which the horse is never retired, which binds his mouth closed, artificially effecting a “quiet in the mouth”, and also reducing his ability to avoid the bit.

The training cavesson innovated and prescribed by the Duke is – in form, function, and effect – an industrialized bosal, which, when combined with reins, becomes the functional equivalent of the hackamore (which has gone by various names since being innovated by the Arabs for camels long before either the Spaniards or Newcastle came to it). Combined with the curb bit, what the Duke innovated with his cavesson was an assembly enabling a technique we would recognize in the US as the Californio vaquero/buckaroo two-rein for high school. As with the hackamore, the tackle itself is irrelevant in isolation.

As with the Iberian-derived vaquero’s two-rein progression in the making of finished stock horses, the training reins and the nose piece are eventually obviated by the curb once the horse is truly finished, or bridled, or, as the Duke would have said: dressed or ‘maneged.’